Tripping On Mark McCloud & the Institute of Illegal Images

A chance meeting with the King of LSD Blotter Art...

Wednesday, Harry and I were taking our afternoon stroll when we stopped in front of an old white, weather-beaten, three-story house. Harry was fixated on a smell, probably a chicken bone, so I waited, eying the man sitting on the house’s front steps. The guy – long-haired, over 60-years-old but by how much I couldn’t tell – returned my gaze. His look was friendly.

“Hi, are you the guy who has the insane blotter art collection,” I asked.

“Depends on who is asking,” the man replied with a laugh. It took a few more questions to get a playful “Yes” out of him and a few more for my new acquittance to share his name – Mark McCloud. Mark told me that he’d collecting LSD blotter art for a long time. “How long?” I asked.

“Internally, since the 1960s,” Mark smiled, “Externally, since the 1970s.”

Mark explained that he started dropping acid back when it was legal and became intrigued with one of the main means to deliver the drug to users, blotter paper, specifically the art on them. Mark started collecting sheets of acid to preserve the art, he says. Problem was, Mark was storing the art in his freezer, and whenever he felt a hankering to get out of this world, he raided his “art collection.” So, knowing that he couldn’t eat the picture frames, he started framing the sheets.

In case you are unfamiliar with the psychedelic world. LSD or acid is a psychedelic drug, that you know. It was discovered by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938 and used by psychiatrists to treat alcoholism, addiction, and depression. Some not-so-by-the-books researchers discovered that LSD was more than that, it was a powerful perception shifter, and, if used carefully, a tool for meditation and mind expansion. Scientists and heads spent the 1950s and 1960s trying to figure the drug out.

By the 1960s, LSD was a part of the counterculture scene, especially within rock & roll, where writer Ken Kesey and bands like the Grateful Dead served as psychedelic pied pipers, San Francisco’s Psychedelic Shop a sanctuary, and Owsley Stanley and Timothy Leary gurus. Still legal, acid not only was culturally important, but a good money maker.

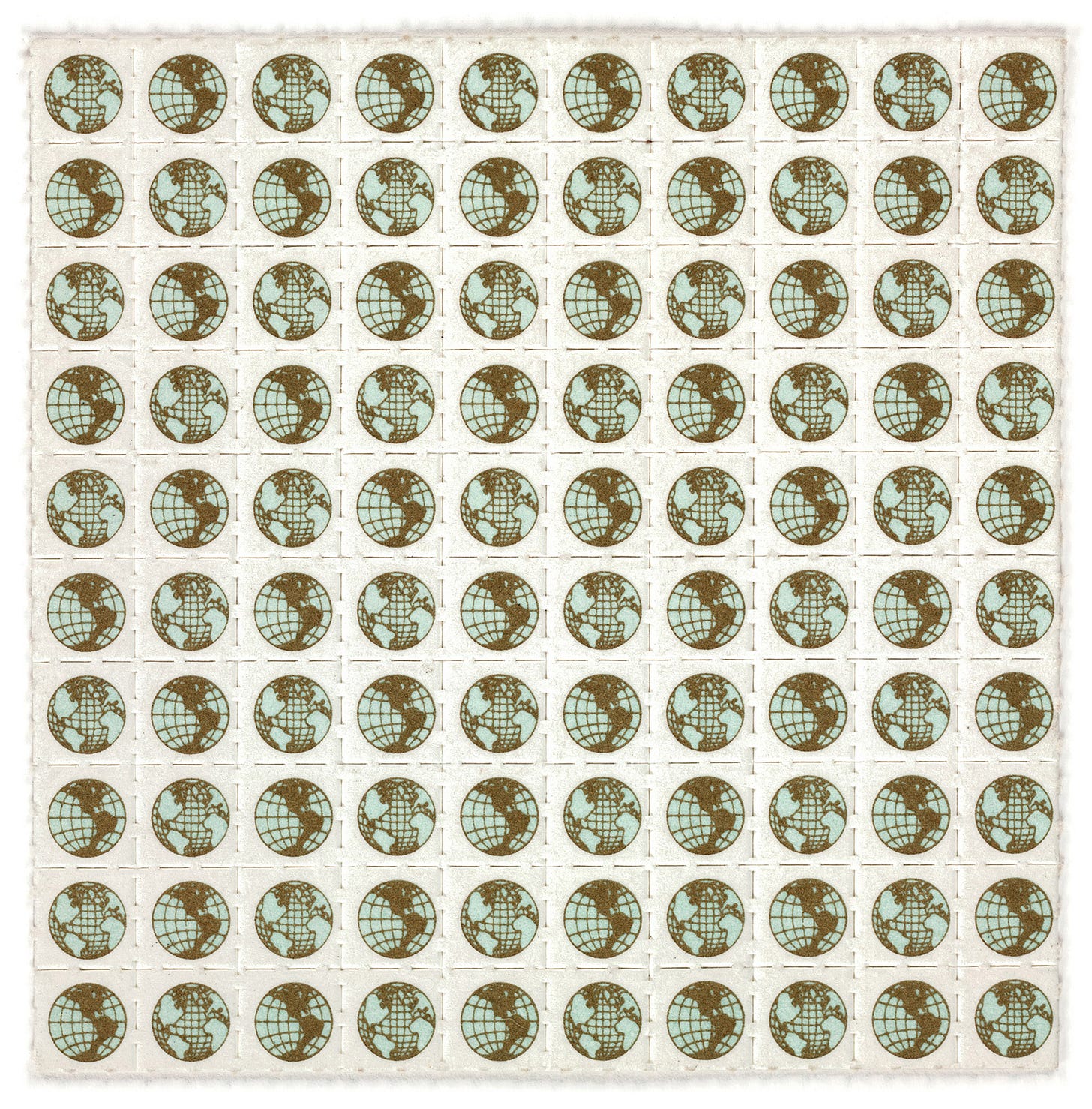

To make max coin, sellers found that the most effective way to move acid was applying it to porous, perforated paper which tore off into half-inch by half-inch squares. The more artistically inclined chemist-manufacturers started printing artwork on blank sheets of blotter paper, something that they soon found was good marketing.

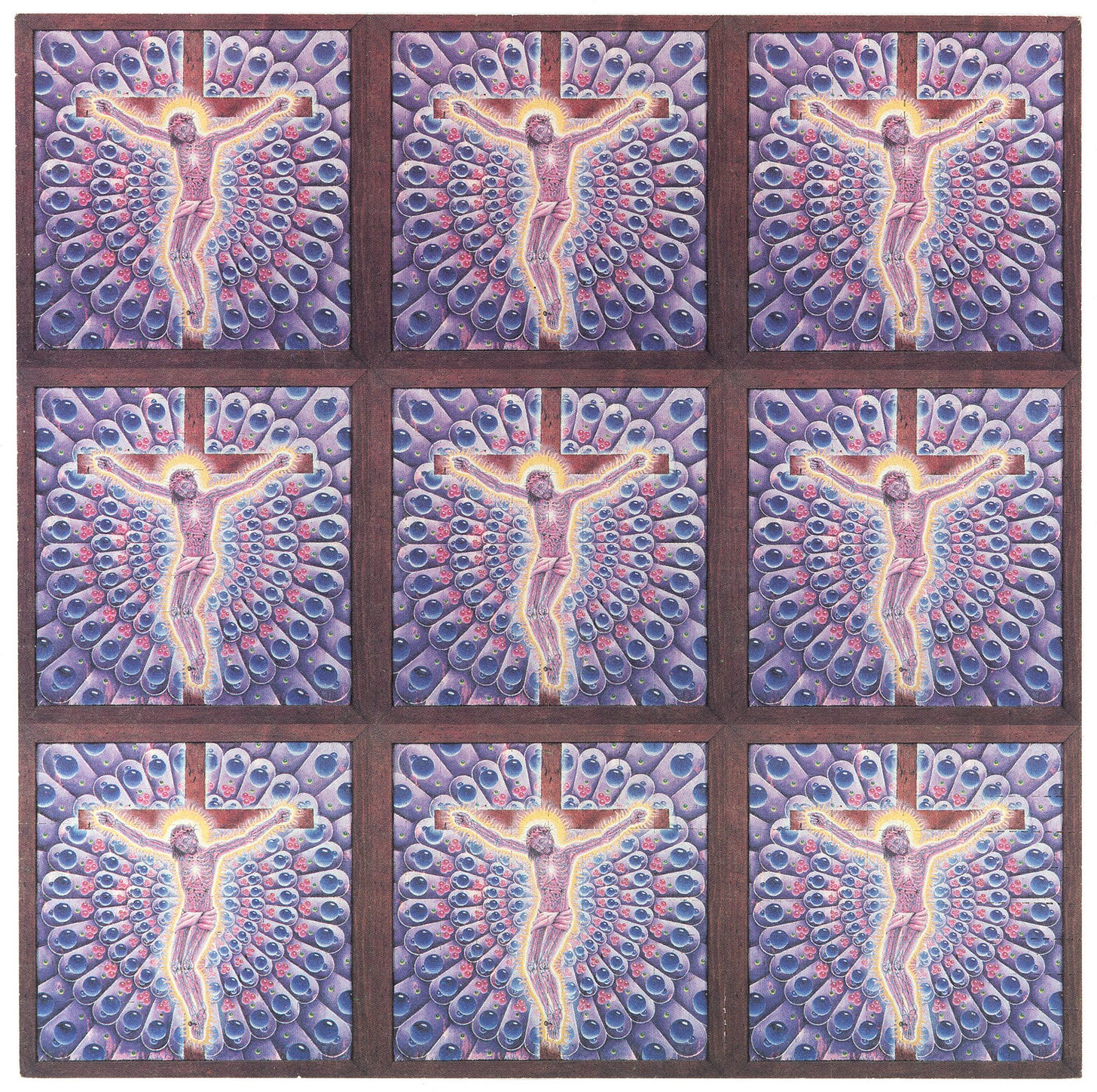

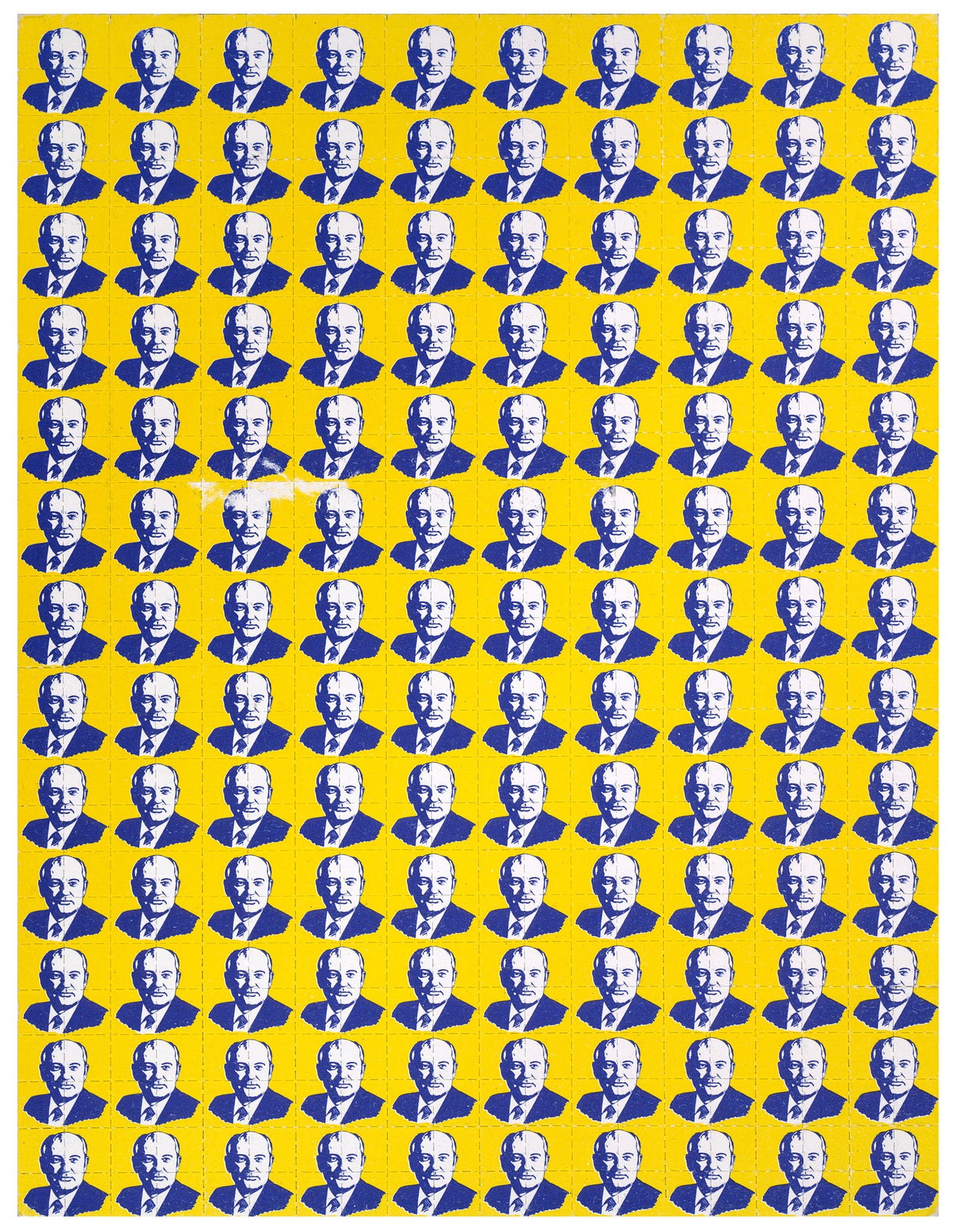

Given that LSD’s customer base was youthful and outside the mainstream, the blotter art tended towards images that appealed to the hippie/youth/rock & roll crowd and/or commented on the psychedelic experience. Characters and images from underground comics were popular, as were skulls and anything that suggested the afterlife. Mythology, especially Eastern and Latin American, was a big source of artwork. So were sayings done in stylized or “foreign” script.

Repeated patterns of abstract but sensual shapes turned up on blotter, as well as surrealist collages. Some sheets were composed of just one image, each half-inch square covered in a fraction of the main image. Often the main image was reproduced on each small square. Mark McCloud was one of the first to recognize blotter art as art, something artistically special and unique. His obsession led him from collecting blotter art to making it.

Starting in the 1960s, McCloud designed and printed sheets of blotter art, which he traded and bartered for more art – blotter as well as psychedelic paintings and sculpture, psychedelic rock posters, etc. Sometimes the paper was treated with LSD, sometimes the paper was “undipped” and chemically neutral.

Until 1968, legally, the paper’s potency didn’t matter much. However, once LSD became an illegal controlled substance, the Fed started cracking down on the psychedelic world. Mark McCloud was well known within psych circles as someone who handled not just blotter art, but acid. He became a target.

McCloud was arrested and sent to trial twice. Even though he faced unfriendly juries, Mark got off both times. Though the Fed nabbed him with blotter paper, government chemists found that Mark’s blotter art collection was chemically inert. There were sheets that hadn’t been “dipped” and ones on which the LSD was so old that it had no effect and was technically not a psychedelic drug. After much hassle and harassment, the Feds started leaving McCloud alone. Free to build his collection, Mark created the Institute of Illegal Images, informally known as the Blotter Barn, LSD Museum or Mark’s house.

After about fifteen minutes of bullshitting, Mark invited me in to see his collection.

Through the front door, the first thing I (nearly) run into is an “acid sculpture” by Ben Ridgway, an oozing, pock-marked orb, bigger than a basketball, set atop a large pedestal. Mark has a couple more of Ridgway’s orbs, as well as a bronze psychedelic Buddha. We turn into the living room and there are other sculptures by other artists, equally as weird as Ridgway’s, along with stacks of crated artwork and binders of psychedelic rock posters.

McCloud’s house is one of those old San Francisco jobs with very high ceilings, which is great because Mark has a lot of framed sheets of blotter art and he needs to hang them somewhere, somewhere being every bit of wall space, from ceiling to floor, in the main room of Mark’s institute.

Obviously, I’ve never been around so much blotter paper, blotter art, or psychedelic inspired stuff. It’s pretty awe inducing. Mixed in with the framed sheets of blotter art are much bigger paintings, some photos and posters, and large images, which Mark says were reduced and reduced until they could be used as blotter art.

I see a shelf stuffed with records. The spine of a box set says Yahowha. “Ohhh Father Yod! That shit is great!” I say. Mark replies, “Sky Saxon was my roommate here, for about a year.” After fronting the Seeds, acid-drenched Sky moved to Hawaii to hook up with Yod, with whom he made music with in Ya Ho Wha 13, Fire, Water, Air, and the Allright Family Band.

“That must have been a trip.” “Oh yeah, it was!” “Nice guy?” “Very nice guy.” I fixate on a portrait of Mark, very busy, very crowded, very psychedelic. “That’s me,” Mark says, “A guy in Argentina made and sent it to me.” “It’s really cool. Looks like it was made by a friendly Joe Coleman,” I reply. “Friendly!” Mark laughs.

Our conversation skips from topic to topic, each segue as smooth as an organic trip through each other’s mind (no drugs were taken in my visit, at least by me. I can’t speak for Harry or Mark). Sky Saxon, Joe Coleman, Blue Cheer, which leads us to V. Vale and Search & Destroy magazine, whom Mark wrote for, something I didn’t know.

The doorbell rings. A delivery driver has Mark sign off on a Rick Griffin piece of art, which I unfortunately do not get to see uncrated. I notice that Mark has a collection of Ugly Things magazine on a bookshelf. I tell Mark that I’ll drop by some copies of my magazine Record Time after I take Harry home.

We split. I drop Harry off, grab the mags, and walk back to Mark’s place. Knock knock knock. Mark answers the door with a very fat spliff hanging from his mouth. I lay the zines on him, he thanks me, I take off and think about how wonderful life can be when we ignore fear of the unknown and of strangers, and actually start a conversation by saying “Hello” and asking a question.

One very simple, friendly exchange and I am in a world that I had never encountered, guided by a very interesting person. My joy tempers when I remember that while people like Mark McCloud still live in San Francisco, their numbers are much smaller than they once were, not because freaks like us do not exist, but because the city is so expensive that when a Mark McCloud moves away or moves on, no junior freak can afford to take his space.

The internet was sold to us as one great big, global meeting place, a space where underground communities can flourish and where everything can be shared in this new technological utopia. And, although a ton of us bought this dream, it turned into a nightmare. Worse is that we were so conned into believing the Tech Propagandists that we abandoned our spaces in the real world – meeting places, brick & mortar stores, performance spaces, newspapers and magazines, independent cultural scenes, etc. – and then got priced out. That never had to be, nor does it have to stay that way.

As much of a bummer as it is that the San Francisco that was once full of people akin to Mark McCloud is no more, people like Mark exist and continue to do their thing regardless of what shit is happening around them, and, in Mark’s case, how hard the authorities come for them. And that is because though Mark McCloud might be the grass growing out of sidewalk cracks, but his roots are healthy and deep. We are who we are regardless of who the president of the United States is or what crazy shit he’s saying. We cannot forget that. We must embrace and live it.